Journal Volume 6 2010

Sir William F. Butler (continued/11)

The Campbell Divorce

Lord Colin Campbell, son of the Duke of Argyll, had been judicially separated from his wife of two years on grounds of his cruelty towards her. In revenge he set about trying to obtain evidence of her adultery. He started proceedings citing numerous well known public figures such as Captain Shaw, chief of the fire brigade, Dr. Bird, a prominent doctor, the Duke of Marlborough and Sir William Butler. She in turn sued him on grounds of adultery with a housemaid for which the evidence was more substantial. The case was sensational and occupied pages upon pages of the popular press. In the end a hung jury dismissed both petitions. However Butler’s reputation was smeared because he refused to appear as a witness. The press verdict was that he was guilty. In fact those who knew him were of the opinion that he abstained from defending his reputation because he knew that Lady Campbell had been indiscreet with someone of his acquaintance and feared that this might be exposed under cross examination. He was pilloried in the press but he remained impervious to criticism. The verdict of those who admired him were that he was firstly, a man of honour and unlikely to have been implicated and secondly that he refused to lend himself to a circus staged by people whom he held beneath contempt.

The Delgany Interlude

In 1888, after 18 months on half pay and no prospect of further military employment, Butler moved his family from Brittany to Delgany, Co Wicklow. His book ‘Campaign of the Cataracts’ had been published in 1887 and he was now working on his life of General Charles Gordon. It was an idyllic time for the family. They roamed the Wicklow hills and Butler befriended Parnell who invited him to stay at his lodge in Aughavannagh for the grouse shooting. Butler considered Parnell one of the greatest men of his era and pays effusive tribute to him in his autobiography.

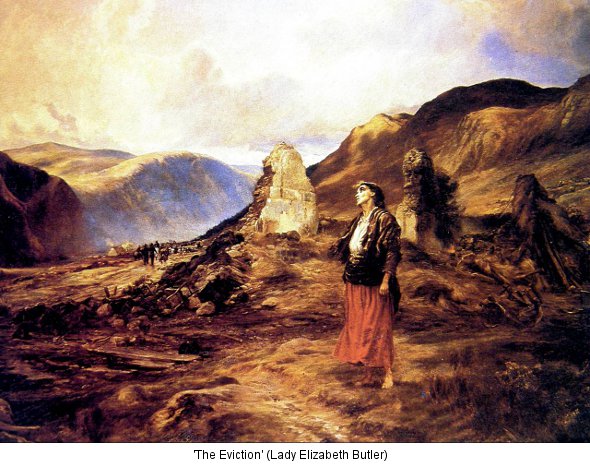

It was also during this time that Lady Butler painted the famous picture ‘The Eviction’. It was at the height of the Land War about which both she and her husband felt very deeply. For the first time one of her pictures was not well received in England. Indeed the notorious Lord Salisbury, Prime Minister of the time sneered that he admired the ‘breezy beauty’ of the scene and wished he could take part in an eviction himself.

During this time the coercion policies of the Tory Government, the failure of Gladstone’s efforts at land reform and home rule, the smearing and downfall of Parnell were blows against the values closest to Butler’s heart. Nevertheless he was a professional soldier and when his old friend Wolseley offered him the command at Alexandria he was delighted to accept

Alexandria 1890 - 1893

Butler spent almost 4 years in Egypt during which time he travelled indefatigably in the region studying its history, its agriculture, social organization and economy, and recording perceptive impressions of what he saw. He also visited the Holy Land and wrote in his usual poetic style his impressions of the holy places. During this time he also travelled extensively in Europe visiting the scenes of the great battles of the Napoleonic era - Arcola, Marengo, Austerlitz, Wagram, etc. Butler hero worshipped Napoleon, obviously as the epitome of the successful professional soldier and these battlefield tours allowed him to study the ground on which the master tactician had achieved his greatest triumphs. It is noteworthy that Butler never visited Russia and does not anywhere comment on Napoleon’s disastrous invasion of that country. He may well have read the recently published ‘War and Peace’ in which Tolstoy displays his contempt for Napoleon – sentiments diametrically opposite to Butler’s.

Aldershot

In 1893 Butler returned to England to take command of a brigade of infantry at Aldershot. He describes the training systems in use by the British Army of the day as relics of the Crimean War – ‘massed divisions, shoulder-to-shoulder tactics, parades, plumes, drums beating, etc.’ which were to bring about the disasters of the Boer campaigns. He describes with grim amusement the useless inspections by ‘old dodderers’ and some of his yarns are really funny.

Around Christmas of 1895 Butler led his brigade on a route march to counteract the effects of ‘pudding and plenty’. During the march an officer riding alongside him revealed that an invasion of the Transvaal was about to take place by white irregulars led by Dr Jameson. At the time the Colonial Office under Chamberlain had aspirations to unite all of the British Southern Africa territories into a great confederation but the resistance of the Boers, and the interests of the African tribes in Bechuanaland and Lesotho were obstacles. The white settlers, ‘the Uitlanders’, were determined to force the government’s hand. It appears that conspirators in England financed by Cecil Rhodes provided them with an inventory of the most modern military equipment. A force of 600 men was to capture Pretoria. Butler, who knew the territory and the capability of the Afrikaner farmers said:

‘You may go to London and tell your friends that those fine fellows who are about to invade the Transvaal will get the most infernal dusting they ever had in their lives.’

And so it came to pass, Jameson and all his officers were prisoners of the Boers.

For the next two years the South African situation simmered with the Government talking of peace and progress whilst some officials in the Colonial Office abetted by others in the War Office were laying plans for further military action.